do mirror neurons in mice exist?

27 Mar 2020 | by @tucetombaz

Several years ago, we embarked on a journey to look for mirror neurons in mice, i.e. cells that fire both when an animal performs a certain action and when it observes another doing the same. Our starting point was the seminal work done in non-human primates over the last 30 years. These neurons were initially uncovered in the macaque ventral premotor cortex, and later also in the rostral part of inferior parietal lobule, among other structures. The regions in question are not only reciprocally connected, but are also implicated to be innervated by similar inputs across the brain. Mirroring representations in these areas have primarily been studied in the behavioral context of reaching and grasping, due to prior explorations of their coding properties.

So, we have cells in our brains that seem to respond similarly when we, say, grasp a piece of fruit and bring it to our mouths, and when we observe our friends performing the same action. Does that reveal something fundamental about the workings of the nervous system and/or social cognition? Some people tend to believe that the described mechanism could physiologically underlie a complex phenomenon like empathy, but there are also others who criticize such views intently. Additionally, one might wonder how a mirroring system could develop and what its biological hallmarks would be. Due to difficulties inherent to primate research, there has been little investigation aimed at teasing the mirror circuitry apart. Our ambition was to counteract this by studying such curiosities in rodents, who possess the prerequisite cortical networks and are amenable to a variety of sophisticated techniques. You can read all about our efforts here.

Briefly, we used optical imaging to sample single cell activity from parietal and secondary motor cortices of mice repeatedly performing a version of the pellet-reaching task and observing their siblings doing the same while they were being head-fixed (check out the animation below to see what this actually looked like).

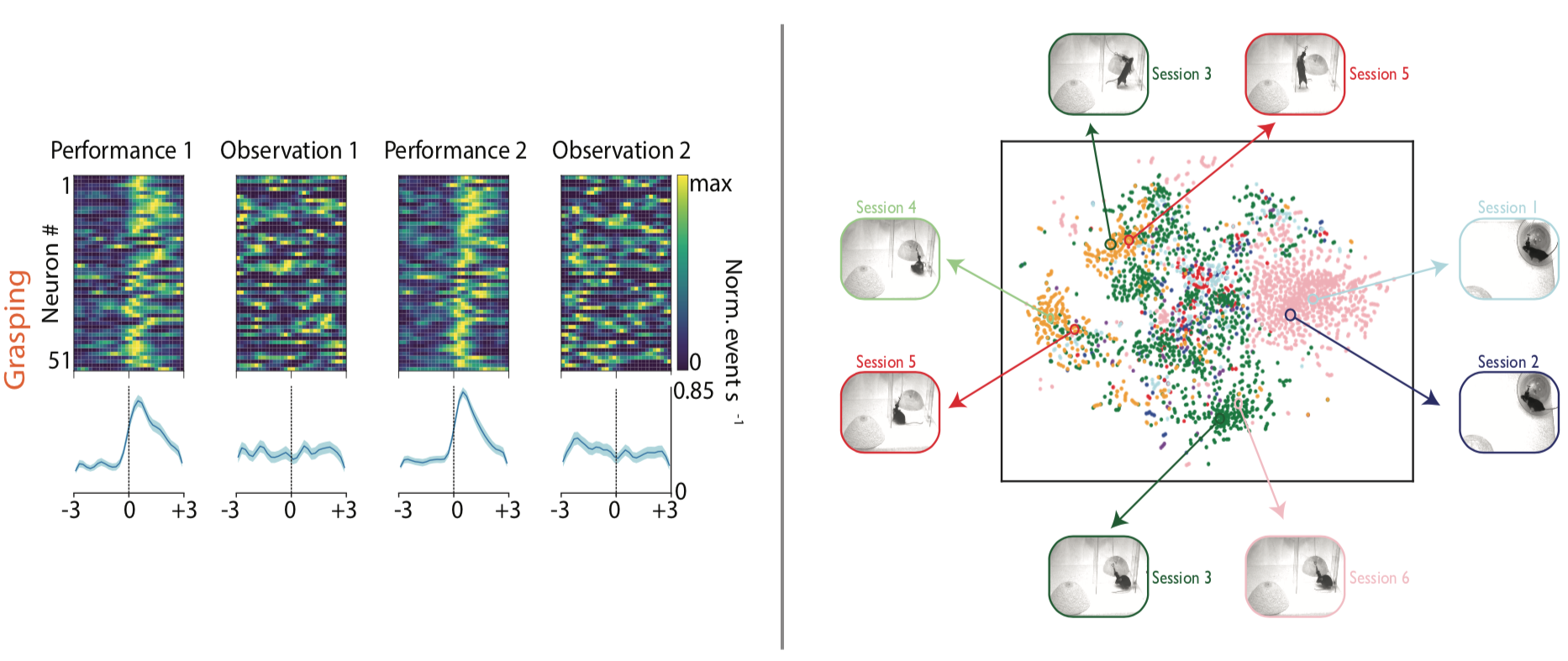

We evaluated the neurons’ tuning properties in different ways. The behaviors of animals in both conditions were carefully and extensively quantified. These detailed analyses revealed potentially important differences between the coding of action execution, as opposed to that of action observation (see figure below: left). Even at the population level, the activity was better clustered in hyperspace when the animals were freely performing the actions, compared to when they were head-fixed and observing a sibling (see figure below: right). Therefore, in this project, we failed to demonstrate the existence of mirror neurons in the rodent associative cortices.

The negative result outcome could, of course, be interpreted in different ways, and it led us to reflect on the limitations of our work. Some of these limitations were clear from the outset and some became more apparent during the review process (thus, we appreciate our reviewers’ and editors’ comments). To simplify, I would just elaborate on the two main ones.

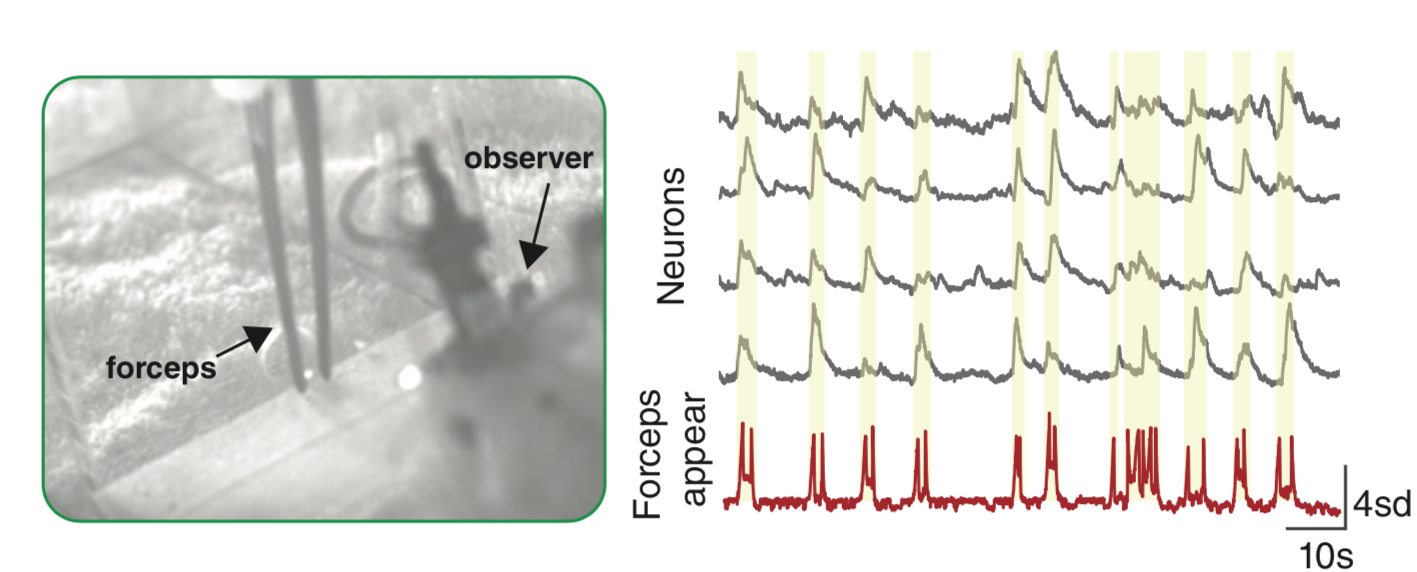

How do you know that mice can see sufficiently well, given what we know about their visual system? This is a fair point, and we attempted to address it by showing that mice respond (both neurally and behaviorally, see figure below) to visual cues at these distances (<15cm), and also by tracking their pupils and taking that covariate into account in our analyses. It is also worthy to point out that there is a big shift towards studying the mouse visual system, with the ultimate goal of understanding how vision works generally. This comes with its caveats, but also its strengths.

Why not study more ethologically relevant behaviors than grasping, which may not be important in the social life of mice? This is another astute point which should be considered before similar undertakings in the future. In our defense, we took into account all the behaviors the animals performed in the pellet reaching task, not just grasping for food. Our approach was undoubtedly motivated by the early primate studies and we wanted to draw a parallel between the studied brain areas and the behavior across species, but this may not have been the best strategy. Mice value social stimuli differently from primates, such that a completely different set of behaviors, say those related to the maternal instincts, might have been more apt for the purpose of our explorations.

In the end, we would like to point out our allegiances to the old truism: the absence of evidence should not be mistaken for evidence of absence. And until new findings emerge, we can gracefully sit on the fence.